What Effect Did Religion Have on the Arts During the Time of Thhe Soguns

9th century Byzantine mosaic of the Hagia Sophia showing the epitome of the Virgin and Child, one of the first mail-iconoclastic mosaics. It is fix against the original golden groundwork of the sixth century

Religious art is artistic imagery using religious inspiration and motifs and is often intended to uplift the listen to the spiritual. Sacred art involves the ritual and cultic practices and practical and operative aspects of the path of the spiritual realization within the artist'south religious tradition.

Buddhist art [edit]

Buddha statue in Sri Lanka.

Buddhist art originated on the Indian subcontinent post-obit the historical life of Siddhartha Gautama, 6th to 5th century BC, and thereafter evolved by contact with other cultures as it spread throughout Asia and the world.

Buddhist art followed believers as the dharma spread, adjusted, and evolved in each new host country. It adult to the due north through Primal Asia and into Eastern Asia to form the Northern branch of Buddhist art.

Buddhist art followed to the east as far as Southeast Asia to form the Southern branch of Buddhist art.

An example of Tibetan Buddhist fine art: Thangka Depicting Vajrabhairava, c. 1740

In India, the Buddhist art flourished and fifty-fifty influenced the development of Hindu art, until Buddhism nearly disappeared in India effectually the tenth century due in part to the vigorous expansion of Islam alongside Hinduism.

Tibetan Buddhist art [edit]

Virtually Tibetan Buddhist artforms are related to the exercise of Vajrayana or Buddhist tantra. Tibetan art includes thangkas and mandalas, often including depictions of Buddhas and bodhisattvas. Creation of Buddhist art is commonly washed equally a meditation every bit well as creating an object equally help to meditation. An example of this is the creation of a sand mandala by monks; before and subsequently the construction prayers are recited, and the form of the mandala represents the pure surroundings (palace) of a Buddha on which is meditated to train the mind. The work is rarely, if ever, signed by the artist. Other Tibetan Buddhist art includes metal ritual objects, such every bit the vajra and the phurba.

Indian Buddhist art [edit]

Two places advise more than vividly than whatsoever others the vitality of Buddhist cave painting from well-nigh the 5th century Advertisement. One is Ajanta, a site in India long forgotten until discovered in 1817. The other is Dunhuang, one of the great oasis staging posts on the Silk Route...The paintings range from at-home devotional images of the Buddha to lively and crowded scenes, oft featuring the seductively full-breasted and narrow-waisted women more familiar in Indian sculpture than in painting.[ane]

Christian art [edit]

Christian sacred art is produced in an attempt to illustrate, supplement and portray in tangible form the principles of Christianity, though other definitions are possible. It is to make imagery of the different beliefs in the globe and what it looks like. Most Christian groups use or have used art to some extent, although some have had stiff objections to some forms of religious paradigm, and there have been major periods of iconoclasm within Christianity.

Most Christian art is allusive, or congenital around themes familiar to the intended observer. Images of Jesus and narrative scenes from the Life of Christ are the most common subjects, especially the images of Christ on the Cross.

Scenes from the Erstwhile Testament play a part in the fine art of most Christian denominations. Images of the Virgin Mary, holding the infant Jesus, and images of saints are much rarer in Protestant fine art than that of Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy.

For the benefit of the illiterate, an elaborate iconographic system adult to conclusively identify scenes. For example, Saint Agnes depicted with a lamb, Saint Peter with keys, Saint Patrick with a shamrock. Each saint holds or is associated with attributes and symbols in sacred art.

History [edit]

Virgin and Child. Wall painting from the early on catacombs, Rome, 4th century.

Early Christian art survives from dates nigh the origins of Christianity. The oldest surviving Christian paintings are from the site at Megiddo, dated to around the year 70, and the oldest Christian sculptures are from sarcophagi, dating to the beginning of the second century. Until the adoption of Christianity by Constantine Christian fine art derived its fashion and much of its iconography from pop Roman fine art, but from this point grand Christian buildings built nether purple patronage brought a need for Christian versions of Roman elite and official art, of which mosaics in churches in Rome are the most prominent surviving examples.

During the development of early Christian art in the Byzantine empire (see Byzantine fine art), a more abstruse aesthetic replaced the naturalism previously established in Hellenistic art. This new mode was hieratic, meaning its primary purpose was to convey religious meaning rather than accurately render objects and people. Realistic perspective, proportions, calorie-free and color were ignored in favour of geometric simplification of forms, reverse perspective and standardized conventions to portray individuals and events. The controversy over the use of graven images, the interpretation of the Second Commandment, and the crisis of Byzantine Iconoclasm led to a standardization of religious imagery within the Eastern Orthodoxy.

The Renaissance saw an increase in monumental secular works, but until the Protestant Reformation Christian art continued to be produced in great quantities, both for churches and clergy and for the laity. During this time, Michelangelo Buonarroti painted the Sistine Chapel and carved the famous Pietà, Gianlorenzo Bernini created the massive columns in St. Peter's Basilica, and Leonardo da Vinci painted the Last Supper. The Reformation had a huge consequence on Christian art, quickly bringing the production of public Christian art to a virtual halt in Protestant countries, and causing the destruction of most of the art that already existed.

As a secular, non-sectarian, universal notion of art arose in 19th-century Western Europe, secular artists occasionally treated Christian themes (Bouguereau, Manet). Only rarely was a Christian creative person included in the historical canon (such every bit Rouault or Stanley Spencer). Even so many mod artists such as Eric Gill, Marc Chagall, Henri Matisse, Jacob Epstein, Elisabeth Frink and Graham Sutherland accept produced well-known works of fine art for churches.[two] Through a social interpretation of Christianity, Fritz von Uhde also revived the interest in sacred art, through the delineation of Jesus in ordinary places in life.

Since the advent of printing, the sale of reproductions of pious works has been a major chemical element of pop Christian culture. In the 19th century, this included genre painters such as Mihály Munkácsy. The invention of color lithography led to wide circulation of holy cards. In the modern era, companies specializing in modern commercial Christian artists such as Thomas Blackshear and Thomas Kinkade, although widely regarded in the fine art world every bit kitsch,[3] have been very successful.

The last part of the 20th and the first part of the 21st century accept seen a focused effort past artists who claim religion in Christ to re-establish art with themes that revolve effectually faith, Christ, God, the Church, the Bible and other classic Christian themes as worthy of respect by the secular art globe. Artists such as Makoto Fujimura take had significant influence both in sacred and secular arts. Other notable artists include Larry D. Alexander, Gary P. Bergel, Carlos Cazares, Bruce Herman, Deborah Sokolove, and John August Swanson.[4]

Confucian art [edit]

Confucian art is art inspired by the writings of Confucius, and Confucian teachings. Confucian fine art originated in Red china, and then spread westwards on the Silk road, southward downward to southern Prc and and so onto Southeast Asia, and eastwards through northern China on to Japan and Korea. While it still maintains a strong influence inside Republic of indonesia, Confucian influence on western art has been limited. While Confucian themes enjoyed representation in Chinese fine art centers, they are fewer in comparison to the number of artworks that are virtually or influenced past Daoism and Buddhism.[5]

Hindu art [edit]

Hinduism, with its 1 billion followers, it makes up about fifteen% of the earth's population and as such the civilisation that ensues it is full of different aspects of life that are effected by art. There are 64 traditional arts that are followed that start with the classics of music and range all the style to the application and adornment of jewellery. Since religion and culture are inseparable with Hinduism recurring symbols such as the gods and their reincarnations, the lotus flower, extra limbs, and fifty-fifty the traditional arts make their appearances in many sculptures, paintings, music, and dance.

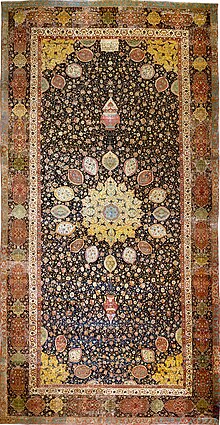

Islamic fine art [edit]

A specimen of Islamic sacred art: in the Swell Mosque of Kairouan in Tunisia, the upper office of the mihrab (prayer niche) is busy with 9th-century lusterware tiles and painted intertwined vegetal motifs.

A prohibition confronting depicting representational images in religious art, likewise every bit the naturally decorative nature of Arabic script, led to the use of calligraphic decorations, which normally involved repeating geometrical patterns and vegetal forms (arabesques) that expressed ideals of lodge and nature. These were used on religious architecture, carpets, and handwritten documents.[6] Islamic art has reflected this counterbalanced, harmonious world-view. It focuses on spiritual essence rather than physical form.

While there has been an aversion to potential idol worship through Islamic history, this is a distinctly mod Sunni view. Western farsi miniatures, along with medieval depictions of Muhammad and angels in Islam, stand as prominent examples contrary to the mod Sunni tradition. Also, Shi'a Muslims are much less balky to the depiction of figures, including the Prophet's as long equally the depiction is respectful.

Figure representation [edit]

The Islamic resistance to the representation of living beings ultimately stems from the conventionalities that the creation of living forms is unique to God. It is for this reason that the role of images and image makers has been controversial.

The strongest statements on the subject of figural depiction are made in the Hadith (Traditions of the Prophet), where painters are challenged to "breathe life" into their creations and threatened with penalization on the Day of Judgment.

The Qur'an is less specific simply condemns idolatry and uses the Arabic term musawwir ("maker of forms", or artist) as an epithet for God. Partially as a effect of this religious sentiment, figures in painting were often stylized and, in some cases, the destruction of figurative artworks occurred. Iconoclasm was previously known in the Byzantine menstruation and aniconicism was a feature of the Judaic world, thus placing the Islamic objection to figurative representations within a larger context. As decoration, however, figures were largely devoid of any larger significance and perhaps therefore posed less challenge.[seven] As with other forms of Islamic ornamentation, artists freely adapted and stylized basic homo and animal forms, giving rise to a great diversity of figural-based designs.

Arabesque [edit]

| | This section is empty. You can help by adding to information technology. (October 2018) |

Calligraphy [edit]

Calligraphy is a highly regarded element of Islamic fine art. The Qur'an was transmitted in Arabic, and inherent within the Standard arabic script is the potential for ornamental forms. The employment of calligraphy as ornament had a definite artful entreatment but ofttimes also included an underlying talismanic component. While most works of art had legible inscriptions, not all Muslims would take been able to read them. One should always keep in mind, nevertheless, that calligraphy is principally a means to transmit a text, albeit in a decorative course.[8] From its uncomplicated and primitive early examples of the 5th and 6th century AD, the Arabic alphabet adult chop-chop after the rise of Islam in the seventh century into a beautiful form of art. The master two families of calligraphic styles were the dry styles, called generally the Kufic, and the soft cursive styles, which include Naskhi, Thuluth, Nastaliq and many others.[9]

Geometry [edit]

Geometric patterns make up one of the three nonfigural types of ornamentation in Islamic art. Whether isolated or used in combination with nonfigural ornamentation or figural representation, geometric patterns are popularly associated with Islamic art, largely due to their aniconic quality. These abstruse designs non only adorn the surfaces of monumental Islamic architecture but also office as the major decorative element on a vast array of objects of all types.[x]

Jain art [edit]

Jain fine art refers to religious works of art associated with Jainism. Even though Jainism spread only in some parts of Republic of india, it has made a significant contribution to Indian art and compages.[xi]

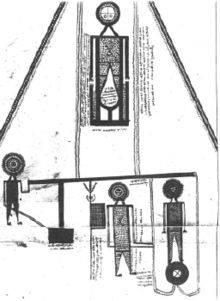

Mandaean fine art [edit]

Mandaean art can be establish in illustrated manuscript scrolls chosen diwan. Mandaean scroll illustrations, usually labeled with lengthy written explanations, typically contain abstract geometric drawings of uthras that are reminiscent of cubism or prehistoric rock art.[12]

Sikh fine art [edit]

The art, civilisation, identity and societies of the Sikhs has been merged with different locality and ethnicity of unlike Sikhs into categories such as 'Agrahari Sikhs', 'Dakhni Sikhs' and 'Assamese Sikhs'; however there has emerged a niche cultural phenomenon that can be described as 'Political Sikh'. The fine art of diaspora Sikhs such as Amarjeet Kaur Nandhra,[13] and Amrit and Rabindra Kaur Singh (The Singh Twins),[14] is partly informed past their Sikh spirituality and influence.

Taoist fine art [edit]

Taoist art (also spelled as Daoist art) relates to the Taoist philosophy and narratives of Lao-tzu (too spelled as Laozi) that promote "living but and honestly and in harmony with nature."[15]

Meet as well [edit]

- Religious image

- Spiritualist art

References [edit]

- ^ "History Of Buddhism". Historyworld.net. Retrieved 2013-09-06 .

- ^ Beth Williamson, Christian Fine art: A Very Brusque Introduction, Oxford University Press (2004), page 110.

- ^ Cynthia A. Freeland, But Is It Fine art?: An Introduction to Art Theory, Oxford Academy Press (2001), page 95

- ^ Buenconsejo, Clara (21 May 2015). "Contemporary Religious Fine art". Mozaico. Archived from the original on 29 September 2015. Retrieved ii June 2015.

- ^ Karetzky, Patricia (2014). Chinese Religious Fine art. Lanham, Physician: Lexington Books. p. 127. ISBN9780739180587.

- ^ "Islamic Art – Islamic Art of Calligraphy and Arabesque". Archived from the original on 2004-02-xviii. Retrieved 2014-02-11 .

- ^ "Figural Representation in Islamic Art | Thematic Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2013-09-06 .

- ^ "Calligraphy in Islamic Fine art | Thematic Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2013-09-06 .

- ^ "Art of Arabic Calligraphy". Sakkal. Retrieved 2013-09-06 .

- ^ "Geometric Patterns in Islamic Art | Thematic Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art". Metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2013-09-06 .

- ^ Kumar 2001, p. i. sfn fault: no target: CITEREFKumar2001 (assist)

- ^ Nasoraia, Brikha H.S. (2021). The Mandaean gnostic religion: worship exercise and deep thought. New Delhi: Sterling. ISBN978-81-950824-1-4. OCLC 1272858968.

- ^ Textile creative person Amarjeet Kaur Nandhra

- ^ Singh Twins Art Launches Liverpool Fest

- ^ Augustin, Birgitta. "Daoism and Daoist Fine art." In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://world wide web.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/daoi/hd_daoi.htm (December 2011)

Further reading [edit]

- Evans, Helen C.; Wixom, William D. (1997). The celebrity of Byzantium: fine art and civilisation of the Centre Byzantine era, A.D. 843–1261 . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN978-0-8109-6507-2.

- Hein, David. "Christianity and the Arts." The Living Church, May 4, 2014, 8–eleven.

- The Vatican: spirit and art of Christian Rome . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. 1982. ISBN978-0-87099-348-0.

- Morgan, David (1998). Visual Piety: A History and Theory of Popular Religious Images. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Sauchelli, Andrea (2016). The Volition to Make‐Believe: Religious Fictionalism, Religious Beliefs, and the Value of Art. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 93, iii.

- Charlene Spretnak, The Spiritual Dynamic in Modern Fine art : Fine art History Reconsidered, 1800 to the Present.

- Veith, Gene Edward, junior. The Gift of Art: the Place of the Arts in Scripture. Downers Grove, Ill.: Inter-Varsity Press, 1983. 130 p. ISBN 978-0-87784-813-4

External links [edit]

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Religious_art

0 Response to "What Effect Did Religion Have on the Arts During the Time of Thhe Soguns"

Post a Comment